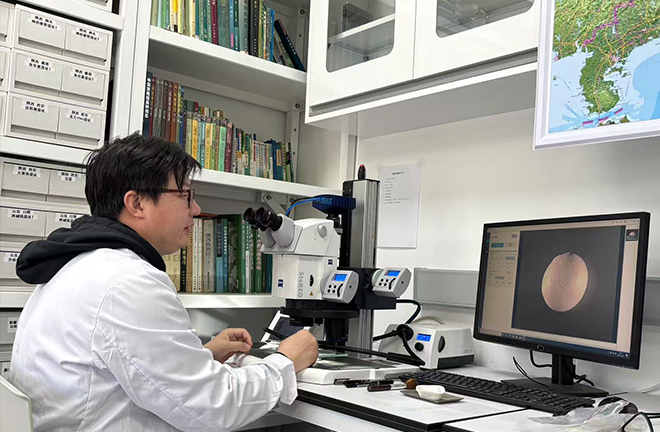

A researcher using a high-resolution imaging microscope to photograph and measure plant seeds Photo: PROVIDED TO CSST

As one of China’s major indigenous genera of drupe-bearing plants, Vitis is well represented in the archaeological record, with remains—primarily carbonized grape seeds—found at sites across the country from the onset of agriculture around 10,000 years ago through to historical periods. However, due to the sporadic nature of plant archaeology findings, systematic research on Vitis remains has long been lacking. Moreover, grape seeds are difficult to classify at the species level, and the plant’s reproductive patterns differ from those of most crops, making it challenging to identify signs of domestication in native Vitis remains. For a long time, such finds were regarded as simply wild resources gathered by early peoples.

‘Vitis vinifera’ species from the West

In China, grapes used for both fresh consumption and winemaking generally refer to the Vitis vinifera species introduced from the West. These grapes have a long history of use in Western Asia and Europe, with the earliest archaeological evidence of domesticated Vitis vinifera found at several early Bronze Age sites in the Levant, dating to around 5,500 to 4,000 years ago. In China, the earliest known presence of Vitis vinifera is from grapevines unearthed at the Yanghai Cemetery in Turpan, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, dating to about 2,300 years ago. Historical texts such as the Book of Songs and the Book of Han also mention the introduction of Vitis vinifera grapes during the Western Han Dynasty.

Prior to the arrival of Vitis vinifera, the ancient Chinese had already begun using native wild Vitis species. Pre-Qin texts like the Book of Songs and Book of Changes frequently reference early grape usage. Of the more than 60 known Vitis species, around 38 are found in China, making the country one of the world’s three major centers for wild grape distribution.

Archaeological discovery of indigenous Chinese grapes

Like the early discovery of Vitis vinifera in Western Asia, archaeological evidence of native Chinese Vitis species includes grape seeds, grapevines (carbonized grape wood), and tartaric acid residues. Of these, grape seeds are the most commonly preserved and frequently unearthed Vitis remains. They have been found across a broad temporal span—from the early Neolithic to historical periods—and throughout much of China’s interior. Most are carbonized, with only a few surviving in extremely dry or waterlogged environments.

In the early to mid-Neolithic (around 10,000 to 7,000 years ago), grape seeds—remnants of foraged plants—were discovered at major sites across China, though typically in small quantities. The size and shape of these seeds varied little between regions, displaying characteristics typical of wild Vitis, such as rounded shapes and short beaks.

Grape seeds appear fairly regularly across China in the late Neolithic (around 7,000 to 5,000 years ago), but their quantities remained small. Interestingly, at sites where they have been found, hunting and gathering remained important components of the subsistence economy, while agricultural systems had yet to fully develop. For example, in the Central Plains, after the formation of a mature dryland millet-farming society during the Miaodigou period (around 5,900 to 5,400 years ago), grape seeds largely disappeared from the archaeological record.

From the late Neolithic to early Bronze Age (roughly 5,000 to 3,500 years ago), grape seeds were most often found at sites along the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River, the upper and middle reaches of the Huai River, and the lower reaches of the Yangtze River. By this time, these regions had developed relatively mature agricultural systems, and hunting-gathering played only a minor role. Although grape seeds remained relatively rare in Central Plains and Haidai region sites [roughly corresponding to the coastal plains and upland areas of Shandong Province], they were more commonly found in the regions mentioned above. In several Liangzhu culture sites in the south, grape seeds appeared frequently, and in significantly greater quantities than during the late Neolithic.

‘Vitis vinifera’ and indigenous ‘Vitis’ species coexisted

From the start of the historical period—especially during the Western Han Dynasty—Vitis vinifera grapes began to be introduced into China. Based on the limited archaeological evidence available, it appears that both Vitis vinifera and indigenous Vitis species coexisted during the Western Han and continued to do so through the Tang and Song dynasties. The arrival of Western grapes did not lead to the immediate disappearance of native varieties. Indigenous grapes continued to be found across a wide area, from the northeastern to the southern coastal regions, while Vitis vinifera remained concentrated in the northwest.

In most fruit tree species, domestication is typically reflected in seeds becoming more elongated [an increase in length-to-width ratio] and having a more pointed base, allowing for a greater portion of fruit flesh. However, seed data from indigenous grapes across different sites and periods shows considerable overlap in shape and size, with no clear chronological trend in the length-to-width ratio. This suggests that seed morphology changed little over time and that native grapes continued to be used at least through the Tang and Song periods, even after Vitis vinifera was introduced.

Were indigenous grapes domesticated?

It is generally believed that China’s indigenous Vitis species are wild varieties. At present, no accepted standard exists for identifying domesticated varieties of these native grapes. Many plant archaeologists argue that, based solely on seed morphology, it is difficult to distinguish between wild and early domesticated grapes. However, aside from size and shape, domesticated Vitis remains can also be identified by other biological and morphological features. Because most Vitis remains in Chinese archaeological contexts are carbonized seeds, and DNA extraction from such material is difficult, determining pollination and reproductive methods or genetic changes is currently a major challenge.

Does the absence of clear domestication traits suggest that indigenous Vitis species were never cultivated in ancient China? Before discussing this, it is important to clarify that in plant archaeology, “domestication” refers to a special evolutionary process influenced by human intervention, leading to changes in a plant’s biological traits and morphological features. Cultivation, on the other hand, emphasizes the human actions taken to promote plant growth, such as planting and managing, without necessarily changing the plant’s traits.

Although the domestication attributes of early grape remnants are difficult to ascertain, we believe that, based on existing archaeological evidence, it is likely that ancient Chinese societies began actively managing and possibly cultivating indigenous Vitis species from the late Neolithic to the early Bronze Age. This conclusion is based on three key observations.

First, analysis of the temporal and spatial distribution of grape seeds in the Central Plains suggests that from the Longshan period (around 4,350 to 3,950 years ago) to the Erlitou period (around 3,800 to 3,500 years ago), the large-scale discovery of grape seeds in this region does not closely correspond to hunting-gathering economies or traditional dryland agriculture. Rather, it reflects a new mode of utilizing plant resources. Remains of drupes-bearing plants, represented by the Vitis genus, are commonly found in sites from this period, suggesting intensified management and even cultivation of fruit plants by ancient populations.

Second, in addition to grape seeds, carbonized grapevine wood has also been discovered at sites like Erlitou. Taking the Erlitou site as an example, not only were grape seeds discovered at this site, but archaeological evidence of wood also revealed the presence of carbonized grapevine wood fragments. The simultaneous appearance of grape seeds and grapevines largely reflects the possible cultivation of Vitis plants in or around the site. Numerous other stone fruit pits, including those of sour jujube, Chinese dwarf cherry, and peach, have also been unearthed from Erlitou layers, along with correspondingly large quantities of charred wood from these plants.

The third reason lies in the increasing social complexity and regional exchanges from the late Longshan to Erlitou periods. The rapid development of society may have driven the management and cultivation of early fruit tree resources.

The use of fruit plant resources varies from that of crops, as the stages of planting, management, and harvest can span several years. On one hand, this requires a relatively stable agricultural settlement system as its foundation. On the other hand, for fruit resources to supplement the economic system, the primary food supply within that system must be securely guaranteed. At the same time, active exchange and trade networks between sites also played an important role in the cultivation of perishable fruit crops. Some scholars have noted that fruit trees, like wool, milk, and other secondary animal products, were regarded as important “cash crops,” widely appearing in societies after the formation of early agriculture and before the rise of urbanization. These goods were mainly used for exchange and trade rather than local consumption. Represented by the Central Plains and the lower Yangtze River region, highly developed complex agricultural societies, through active and prosperous internal exchange networks, provided the possibility for the cultivation of Vitis plants.

Long before the introduction of Western grapes, China had been utilizing native grape resources for millennia. Even after Vitis vinifera arrived, it did not fully replace indigenous varieties; both types coexisted for a long period. From the late Neolithic to early Bronze Age, key regions with relatively advanced agriculture and social complexity—such as the Erlitou site in the Central Plains—likely began cultivating fruit trees, including Vitis. The scene described in the Book of Songs—“In June, we eat oriental bush cherries and wild grapes”—may well have been a common one in the Central Plains more than 3,000 years ago.

Zhong Hua is an assistant research fellow from the Key Laboratory of Archaeological Sciences and Cultural Heritage at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Edited by REN GUANHONG