China’s unique wartime experience deserves further research

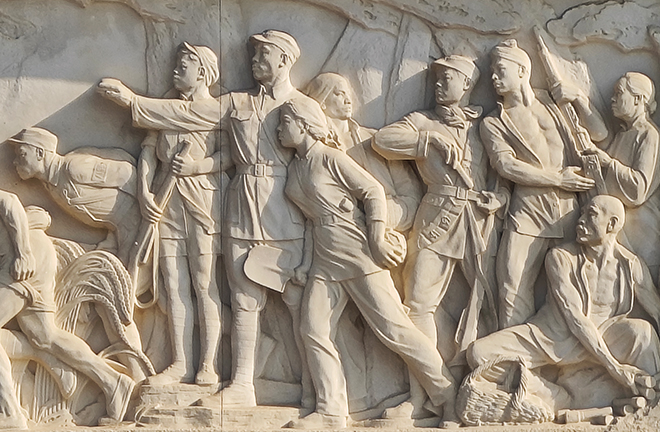

A marble relief titled “Guerrilla War Against Japanese Aggression” on the lower base of the Monument to the People’s Heroes on Tian’anmen Square in Beijing Photo: Tian Jun/CSST

The Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression is still perhaps the aspect of WWII that is least known in the Western world. There are a variety of reasons for this. One is that it was one of the few theaters of war where Westerners were not directly involved in combat, although they were present in other ways. Another is that most of the materials are in Chinese or Japanese, which are still not widely studied languages in Europe or North America. In addition, materials have been hard to obtain.

Yet the situation has improved in recent years. There’s been a slow but steady increase in the visibility of the war years in Anglophone scholarship on the period. From the 1990s onward, key Western scholars such as the late Professor Ezra Vogel of Harvard University worked to bring together scholars from China, Japan, and the West in a joint exercise to understand the history and legacy of the war. A range of Western scholars published important works on China’s wartime experience; among them have been Stephen MacKinnon, but there are many others.

In 2013, I published the book Forgotten Ally: China’s World War II, 1937—1945, which aimed to bring together aspects of the political and social history of WWII in China for a Western readership. I was honored that the book received some attention in Chinese translation, and was considered by some scholars to be a useful addition to wider scholarship on the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression.

In the past decade, there have been more works in the West that have dealt with important aspects of the War of Resistance. One important trend has been the desire to make the war a fuller part of a global history. China’s war is placed in the context of the global struggle, and comparisons are also made with the experience of other countries. The most significant work in the past decade is the Cambridge historian Hans van de Ven’s work. I was a student of van de Ven’s for my PhD and have been learning from his highly innovative interpretations of the war period for many decades now.

The war itself will, we hope, continue to generate strong research for years to come. Key journals within China, such as Studies of the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, continue to publish extensive amounts of research informed by materials from archives and libraries. Much of this work remains hard to access for readers who are unable to read Chinese. It will be important in future to find ways to enable that scholarship to become more accessible to a global academic readership.

New research will also move in part from the wartime period itself to the postwar. For years, there has been rich work on the postwar environment in Europe, with many important books and articles on the reconstruction of Eastern and Western Europe. The literature on postwar Asia has been thinner in general, however. The study of postwar Japan has been genuinely rich, in large part because of open archives and access to materials since the 1950s.

However, there are signs that there is now more openness to exploring some of the questions that emerged in 1945 when the Allied victory was finally assured in Asia. For instance, there is growing interest in the international institutions that emerged from WWII and influenced China’s destiny, and the destiny of Asia, and the wider world. Another institution that emerged at the end of the war was the United Nations. The origins of China’s involvement in the UN come from its participation in the war, leading former US President Franklin D. Roosevelt to insist that China should become one of the four postwar “policemen” of the world alongside the US, the USSR, and Britain. Today, the UN still sits centrally within the international order created in 1945. Understanding the historical origins of China’s presence in the organization has become more, rather than less, important in recent years.

There is still a long way to go before China’s wartime experience is fully integrated into the Western understanding of the global conflict. Yet there are many more studies available now than was the case even a decade ago. Here, comparative social history may be an important element of future historiographical shifts. China’s experience of war should be understood by many outside China itself. For that reason, scholarship on that experience should go further in understanding where China’s experience was unique and where it was comparable to other places in the world.

Rana Mitter is a British historian and a professor from the Harvard Kennedy School.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE